Slow slip events, also known as ‘silent earthquakes', have long fascinated scientists for their potential connection to larger, more destructive earthquakes. Unlike normal earthquakes, slow slip events do not generate strong shaking. While they often go unnoticed by most people, they change the conditions deep in the Earth and can therefore influence whether and where a future earthquake is more or less likely to happen. They happen all over the world, with the slowest recorded earthquake lasting over 32 years in Indonesia.

Detecting Southern Costa Rica’s Hidden Tremors

A new study led by Dr Mason Perry, a Research Fellow at the Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS) at Nanyang Technological University, reveals the first observations of slow slip events in Osa Peninsula, in Southern Costa Rica. The study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, found four events. Two events occurred in early- and late-2018, while the other two occurred in early- and mid-2022.

Dr Perry recounts that this paper was initially drafted back in early 2022, focusing on the two events that had occurred in 2018. But when the team was about to submit the paper, two new slow slip events occurred.

“It was exciting to have more data, but it meant we had to re-do the paper!" said Dr Perry.

The additional set of two slow slip events gave Dr Perry and his team more confidence in their estimation that slow slip events recur at Osa Peninsula every four to five years.

Dr Perry explaining the mechanisms of slow slip events at Osa Peninsula (Source: Jay Wong/Earth Observatory of Singapore)

Leveraging the Unique Geography of Osa Peninsula

Slow slip events often occur at subduction zones, at the boundary of two tectonic plates. Around the world, including Southeast Asia, subduction zones tend to be offshore. Obtaining data of slow slip events close to their source therefore requires extremely specialised and expensive instruments. But the subduction zone near Osa Peninsula is different. It lies very close to the peninsula, which offers a rare opportunity for scientists to study shallow slow slip events using common instruments on land — terrestrial Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) stations.

Better understanding slow slip events and their distribution near Osa Peninsula could help scientists better estimate where a future earthquake is more or less likely to happen in the region. Close observations of slow slip events, as done in Osa Peninsula, can also unravel key mechanisms driving these enigmatic events, which can be applied to other regions, including Southeast Asia.

Monitoring Earthquakes from Across the Pacific Ocean

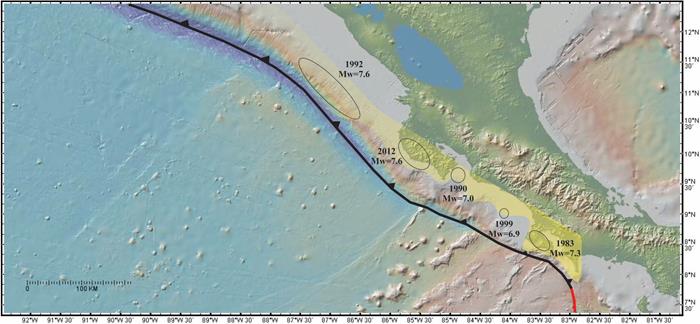

This work was born out of a collaboration between EOS and the Observatorio Vulcanológico y Sismológico de Costa Rica at the Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica (OVSICORI-UNA). It contributes to ongoing monitoring and analysis of tectonic activity along the Osa Peninsula, which has experienced at least three large (magnitude 7+) earthquakes in recent history: in 1904, 1941, and 1983 — in approximately 40-year intervals.

Seismogenic zone and most recent megathrust earthquakes along the coast of Costa Rica (Source: Dr Marino Protti/OVSICORI-UNA)

It is now 40 years since the last large earthquake, and scientists from OVSICORI-UNA have been preparing for future events by improving their monitoring networks. They have densified the regional seismic network and established a continuously operating GNSS network in and around the Osa Peninsula. This translated into very robust datasets that are key to better understand the region tectonics. The study was built from these datasets and the expertise from OVSICORI-UNA.

“OVSICORI-UNA's work in monitoring seismic activities in Costa Rica is invaluable for understanding the region's seismic hazards. This paper would not be possible without their dedication and expertise,” said Dr Perry.

This GNSS station lies just 15 km from the Middle American Trench. It was installed in 2023 at Corcovado National Park in Osa peninsula, as part of OVSICORI-UNA’s monitoring network (Source: Enrique Hernández/OVSICORI-UNA)

Exploring New Horizons

Excitingly, this cross-boundary collaboration will continue beyond this paper.

“Maintaining and processing the data from these networks consumes most of our time and we end up publishing and interpreting only a small portion of that data,” said Dr Marino Protti, seismologist and director of OVSICORI-UNA. “By working with EOS to process, discuss, and interpret our results, we get to achieve much more.”

Dr Perry’s next project aims to develop models to pinpoint locked regions along the same fault, using data from OVSICORI-UNA's network. Locked regions refer to areas of accumulating stress that, when released, can trigger powerful earthquakes. Understanding and monitoring them is crucial for seismic hazard assessments.

Dr Protti hopes that this collaboration is just the beginning. “We would like to have more in-person interactions with our colleagues from EOS, and open the doors of our observatory to students from Singapore who could be interested in having hands-on training on how volcano and seismological observatories operate,” he said. “We will also love to join our colleagues from EOS in their experiments and field projects throughout the Indian Ocean. We still have lots of data that we want to use to replicate the successful experience we had with Mason Perry and his colleagues.”

Commenting on the partnership and its growth, Professor Emma Hill said, “This has been such a wonderful collaboration, and I am looking forward to seeing it continue. I’ve very much enjoyed the regular meetings with our colleagues from Costa Rica, which have been infused with such open, friendly, and scientifically interesting discussion and sharing of knowledge. I think we’ve all learned a lot from working together."

Through international collaborations that leverage on unique datasets and diverse expertise related to slow-slip events, we move closer to understanding where and when slow-slip events might occur, and how they affect the occurrence of potentially damaging earthquakes. The team’s work therefore not only benefits the Osa Peninsula but also offers insights into seismic hazards worldwide, including here in Southeast Asia.